The Strictly Serious Mission of Humorous Criticism

Pablo Helguera

Published the 3 January 2021

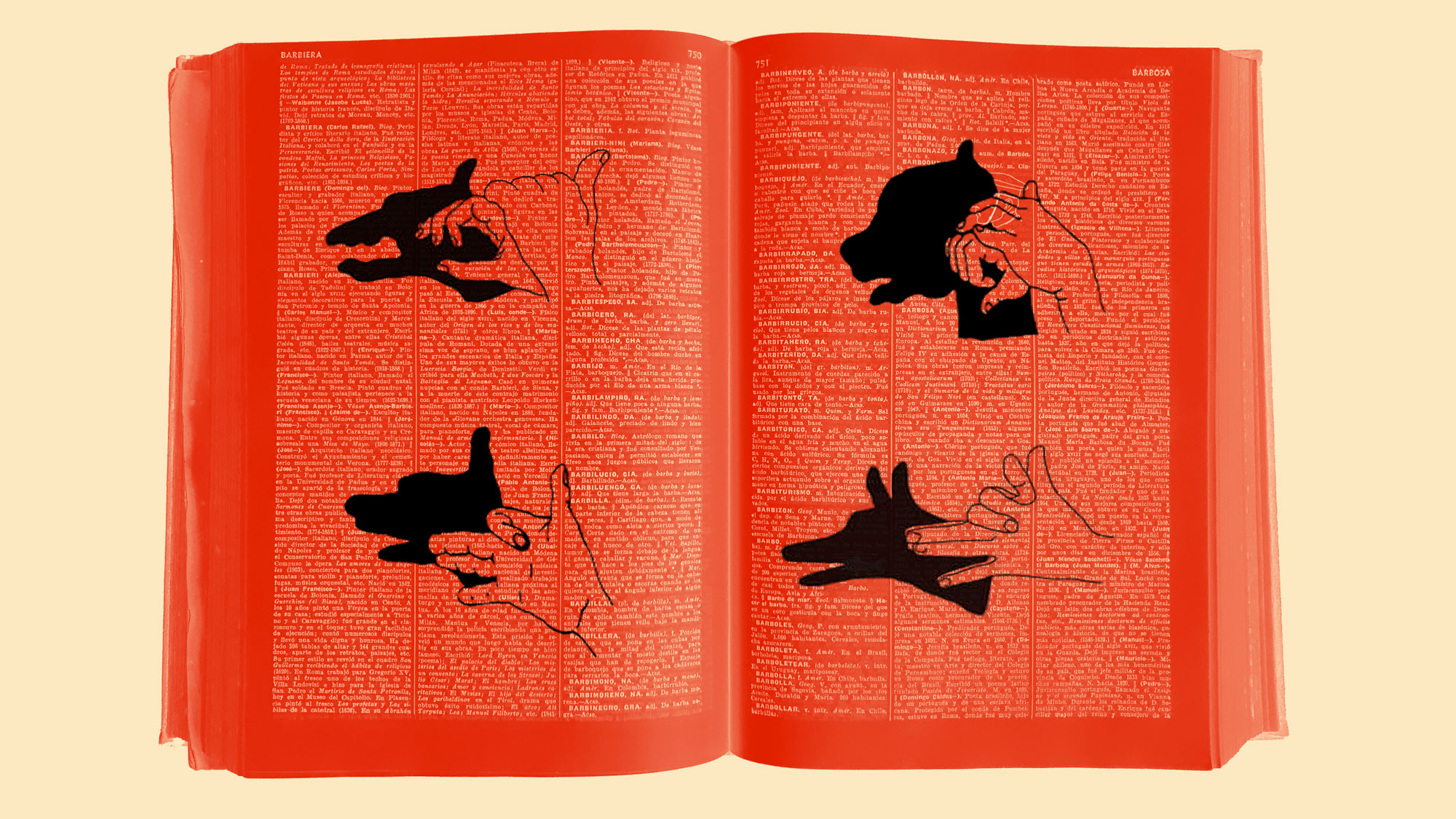

Illustration by Danila Ilabaca

- Can humor unleash serious criticism?

- Can humor transcend the discredit it usually receives for not being subtle and solemn, for its tendency to simplify and use stereotypes?

Cartoons have always been viewed as a minor genre in art. With some exceptions such as the Goya of Los Caprichos, the work of Daumier and Hogarth, what is considered “great art” cannot fall into the satirical representation of stereotypes.

However, I believe that the conflict that the art world has with humor is a bit more complex.

This most likely stems from the paradoxes that Duchamp inserted into art in the early twentieth century. For the avant-garde of those times, it was urgent for art to break with certain prevailing schemes and paradigms related to the manufacture and originality of art. The gesture of inserting a urinal in a gallery breaks with these schemes, but at the same time questions the predominant solemnity of the discourse of art. Still, the prevailing humor in the art world is usually shown as sarcasm or irony. The art world is extremely dependent on roles and hierarchies, and pure humor reverses this state.

The prevailing humor in the art world is usually shown as sarcasm or irony.

On the other hand, humor in contemporary art operates in a two-step process that is common in many works, and that I call “encounter and reflection.” This consists of inspiring a different type of reading than the conventional one that an image or a situation has. Seeing a drawing by Saul Steinberg, or a mischief by Maurizio Cattelan, usually triggers a laugh, or another kind of gut reaction. But these works contain value that goes beyond the first instinctive impact they cause.

William Kentridge said this masterfully at a conference many years ago. He was talking about children hand-shadow theaters. Although I might be paraphrasing his message, he argued that when we see a hand producing a figure that in the projected shadow generates a dog, and we laugh, according to him, we are laughing for three reasons at the same time. First, we laugh because we are looking at a funny or comic figure. Second, we laugh because it delights us to witness the process through which the figure has been made -that is, a twist of the fingers producing the dog’s mouth, ears, and nose. And finally, and this is crucial, we are laughing at ourselves, because we are celebrating our own credulity.

This means that humor in art, in its most effective way, operates on all these registers. It points us towards an absurdity with understandable and simple elements. It is an old joke that we ourselves could tell — that is, the elements that it uses are not exclusive to the virtuoso. But most importantly, it reveals to us that there is something much deeper behind that laugh: it reveals a reflection of the world, sometimes existential, sometimes of a social or political nature, that helps us see the world in a critical way.

In this world in which we are in constant battle against the “truth”, where the facts are constantly manipulated by governments, where the rhetoric of “fake news” is a weapon against neofascism, humor seems to me the most powerful because it makes use of pointing out absurdities that we can all recognize and that at the same time point to much more complex truths. This is the strictly serious mission that humor has.